-

A few days ago, I stepped out of my hotel room at 8.30 and made my way over to Barcelona’s Design Hub, the home of the OFFF event. This is a ridiculously early time to go to OFFF. It’s Spain after all. But today was special. I was taking part in a growing OFFF tradition. Houdini day.

Hats off to SideFX, who make Houdini, and especially Chris Hebert for having the vision to start this event. A few years ago there were three of us speaking. On this day there were more than 10. So we started early. There was still some mist in the air on a day that, of course, would become hot, sunny and joyous. That’s just how OFFF works.

As I headed towards the venue, I saw something I’d never seen before. A group of about a hundred were queuing up next to a side entrance to the enormous brutalist ship that is the Design Hub. Over these years it’s become a bit of a sticking point that getting to the Houdini talks is tricky. It’s the top floor of a big building and crowd control is taken very seriously. In past years, long queues have formed. But I’ve never seen people waiting like this. Like the diehard fans outside a music venue, hours before the show starts.

Eventually I went in. A small group was allowed into the seats. Looking out the window I could see that just as many were still waiting outside. I gave my talk. It went down well. Some lovely people came and said hi afterwards. The talks continued. The queue got longer and longer.

But what has stayed with me. Or perhaps what I’ve been slowly realising for a few years now, is how much my role as a designer/artist has changed. The people watching my talk, and those waiting outside, are as important to me as my clients. I want to inspire/discuss/moan with them, as much as I want to make great work. For a while I thought this made me less of an artist. But now I realise, that’s the real artistry.

Take a look at our business right now. There’s never been more talent crushing digital media. They’re coming from every corner of the planet (I know, I met them). And they’re hungry to learn. That’s why they stand outside on a chilly grey morning. Some of those clouds aren’t made of water vapour. There’s a nimbus of well-funded technologists casting a shadow over this whole scene. They see our world as an easy win. Build software tools that can replace digital artists and you’ll be rich. I have no idea why they expect this to be an attractive proposition within the creative space. It’s sold as somehow democratising filmmaking. Take one look at the people behind this tech and you know straight away democracy is not in their interests.

I use AI in a lot of my work. But not how these guys are selling it. I don’t know what value they think they’re bringing. What I do know is I feel my role as a digital creative is taking a new shape. For me, being original isn’t necessarily about coming up with cool new looks or visual languages - as much as I love those things - it’s about changing the whole way we tell stories and communicate with each other. Being an artist can go beyond making something and putting it out there. It can be making something interactive. Making something that other people then use to make their own art. Sharing knowledge, teaching. Even making a tool, for me, is a form of artistry, as long as it's helping empower our community. One artist I hold in high regard, Simon Holmedal, builds the most intricate Houdini setups for massive clients and then shares them with other artists, not so they can copy him, but so they can learn and become great artists too. I can’t think of a more generous example of artistic expression. That’s what being a rockstar means in our world.

But we can all be rockstars In this community. I call it an ecosystem. We all depend on each other, protect each other and support each other. No one gets left behind. Sure I want to make stuff. But I want to be there for my fellow artists, experts and newbies, just as much. We got this. -

TL;DR = As visual artists confronting AI, we need to forge our own tools that let us exploit this new technology, instead of letting it exploit us.

We’ve all seen the self-proclaimed bellwether posts: ‘Photoshop is dead’, ‘Goodbye concept artists’, ‘Who needs copywriters now?’ We’re being inundated with stories about AI and how it will simultaneously revolutionise the creative world and wreck the careers of everyone in it. But to me, as a digital artist working in visual storytelling, these extreme takes ring hollow.

Is AI going to change the way we work? Probably

Is AI going to change who we are as artists? Not at all.

Behind this is my assumption that those of us who enjoy crafting imagery aren’t about to pack it all in and let machines do our work. Instead we have an important job to do. We need to forge our own tools that let us exploit the new technology, instead of letting it exploit us. It’s crunch time. Read anything about AI image-making these days and you’d be inclined to think that it all boils down to two options: you either let AI completely replace the way you make images and moving pictures (by using full frame text to image tools such as Midjourney) or you begrudgingly allow AI tools to act as co-creators embedded in your software (as with the AI image extension tools in Photoshop for example.) I’m grateful for some of these advances. A tool that can strip unwanted objects out of a shot and create a clean plate is a godsend. But I draw the line when it starts inventing its own content. Unless you enjoy letting a machine make all or most of your creative choices, using AI this way feels like a compromise. But there are other ways, where we still keep creative control but also get a lot of new power.

An animated GIF showing a palette creation tool using ChatGPT

So let’s start with something really simple. I recently made a tool for creating colour palettes using natural language. The user just types in a colour description. It can be anything from stating an actual colour to completely subjective prose. The tool doesn’t mind. It just comes back with a response: a ramp of five colours that sit nicely together. If you like it, you can use it. If not try something else. The AI behind this is the large language model (LLM) ChatGPT. While ChatGPT has a reputation for being less than truthful, it’s a great tool for converting natural language - the way we speak - into structured data like the numbers that describe colours in digital images. The subjectivity doesn’t matter. Colour preferences are subjective anyway, right?

Using LLMs as language-to-data systems in VFX is, to me, an under-appreciated resource. A lot of the drudgery of looking up values can simply be eliminated. What’s the Index of Refraction (IoR) for Perspex? What are the best values for a procedural noise mask for a rusting iron material? Instead of digging out these numbers through searches or trial and error, we can just type in these descriptions in the relevant part of our software and an LLM will plug in numbers. The great bonus is we maintain control. The system populates our setups with the data and values we request and then we can adjust them as we see fit. As digital artists, we’ve trained ourselves to see the world the way a computer does: as numbers. Using an LLM this way actually lets us go back to describing the world as place of colour, form and texture.

In terms of tools, these are quite low-level. They perform small, specific functions, but can be very powerful when used together. They’re the hammers and chisels in our toolbox. But what about the higher-level tools? What’s the compound mitre saw in this world? I guess that depends on where you sit within a creative team or pipeline. Personally I’m looking at ways to reduce some of the heavy lifting in 3D VFX work and let me focus on the story I want to tell. One toolset that’s peaked my interest is called MLOPs. Developed by Bismuth Consultancy and Entagma, MLOPs brings the power of machine learning tools into my go to 3D application, Houdini.

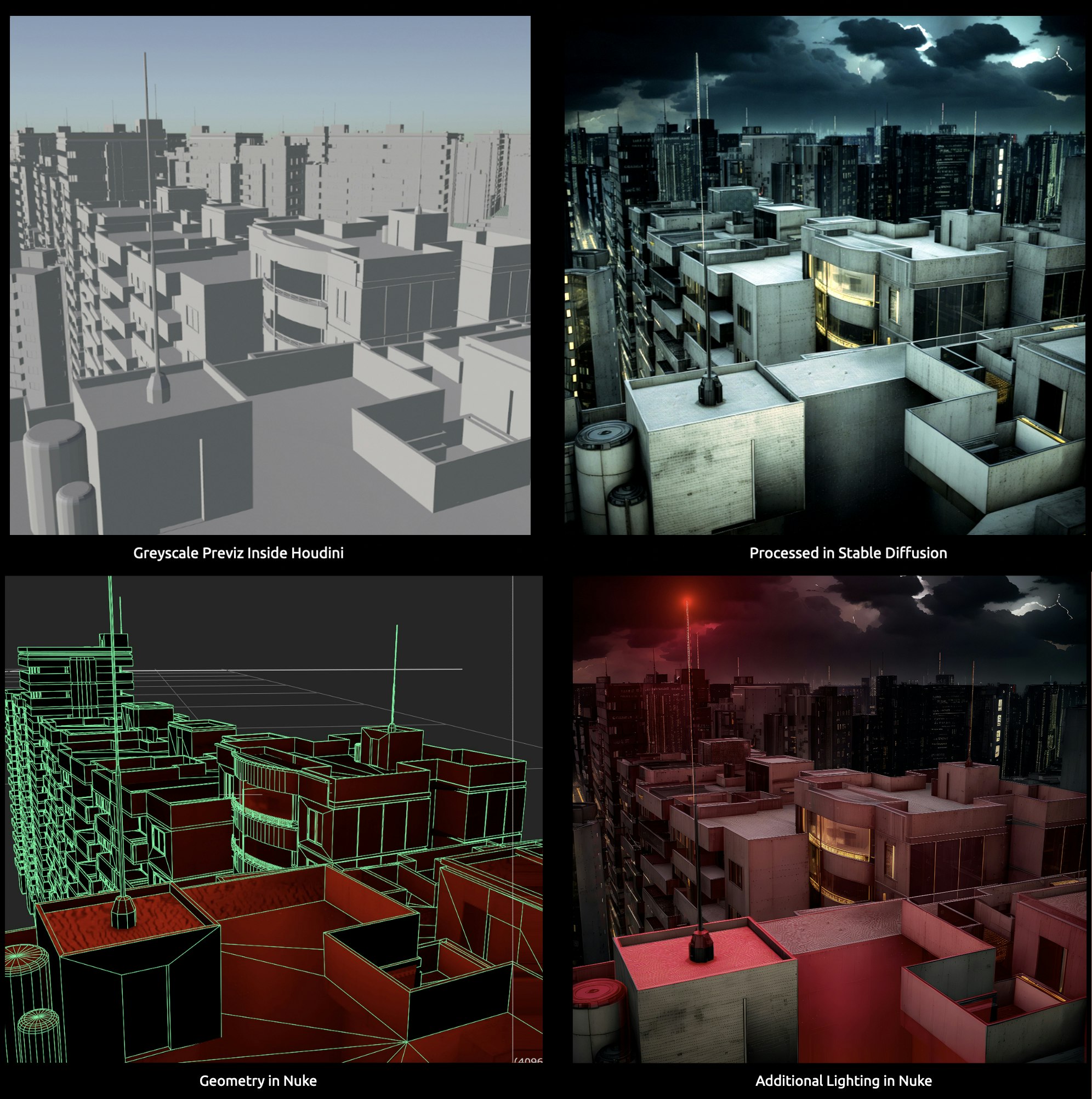

Four images illustrating the use of Stable Diffusion inside Houdini Right now, MLOPs’ main AI engine is Stable Diffusion, an open source machine learning system for making images. At first glance Stable Diffusion could be mistaken for Midjourney, but with slightly less successful output. In reality Stable Diffusion is a much more open system and gives users a lot of interactivity. As well as text prompts, users can feed a broad spectrum of information into Stable Diffusion to guide it. The main route into this is ControlNet. ControlNet allows users to translate guide imagery into specific image formats that Stable Diffusion can understand. For example, working within MLOPs I can build a 3D scene with simple low-detail objects, setup a camera and lens, and then rasterise that scene into images that represent standard 3D render passes such as normal, depth and segmentation maps which identify specific objects within the scene. There’s no conventional rendering in this. MLOPs flattens the scene into passes in realtime. ControlNet can read these passes and convey them as guide information into Stable Diffusion. So suddenly I’ve got an AI image generation system where I control camera, layout and content all working inside the familiar working environment of Houdini. Likewise, I’ve still got all the benefits that come with the actual 3D scene I built. I can move my camera, shift objects around, change the lens - all the subtle control that we typically give up when working with a full frame AI system like Midjourney. Finally I can pass everything from my original 3D geometry and camera, the ControlNet passes, and the Stable Diffusion image output into Nuke, where I can project the AI generated texture back onto my 3D scene and play with lighting and compositing effects. In other words, I’ve not changed my 3D pipeline to accommodate AI. Instead MLOPs has brought the AI tools into my pipeline. A massive difference.

With Stable Diffusion, this is just the tip of an ever-growing iceberg. Being open source, the capabilities of Stable Diffusion are growing at a dizzying pace, mainly thanks to ControlNet and it’s many outputs.

Another valid criticism of AI tools like this is the likelihood that the models were trained on other artists’ material, without their permission. Using art generated this way may or may not legally constitute theft. We’re waiting for the courts to decide that. But as image-makers we need to be conscious of our role in the creative ecosystem. We’re here to invent, not steal. Stable Diffusion does offer one mitigating option: we can train Stable Diffusion models on our own artwork, or work we’re legally entitled to use. Studios or design houses with their own look and even a modest size library of their own images can create their own Stable Diffusion model in less than 24 hours. And MLOPs includes tools to simplify this. This is essential at studios, such as my employer, if we’re to have any chance of verifying the prominence of our creations. While we can’t control how the base Stable Diffusion model has been trained, we can still make it clear that the imagery we’re creating used a model trained on our own body of work, along with scenes we’ve crafted and compositing done by our artists. As we contemplate using these tools on paid work with brand and agency clients, we’re sharing the process with them at every step. It’s essential, morally and legally.

That’s my take. I’d love to hear your thoughts, especially how you’re working with AI tools like this. -

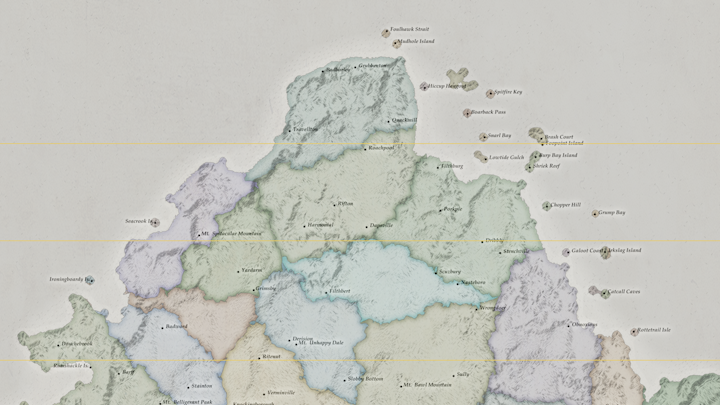

Here's my talk from FMX2023 Houdini Day. Lot's of crazy stuff in here, including how to use ChatGPT to create a rude fantasy map.

The Houdini Idea Machine -

REPRINTED FROM THE MILL'S MEDIUM CHANNEL

Everyone’s got a story to tell. So in The Mill’s Experience Team we’re building custom tools to express individual experiences through physical and virtual clothing. Not just for high-profile football players, but for all of us.

EE Hope United Team Photo Earlier this year, The Mill Experience Team was asked to create a unique garment. Well, actually several unique garments. The creatives at Saatchi and Saatchi behind the Hope United football team were looking for a new way to talk about the online hate and abuse aimed at their players. The idea was to move the murky world of online hate, with its anonymous social media accounts spewing bile at the athletes, out of the shadows and into the public view as data art. We’d monitor the players’ social media accounts, identify and quantify abusive messages, and create a system that would turn this data into designs for the players’ shirts. We’d also measure the hopeful comments, the positivity, love and loyalty from the players’ supporters. Each player would get a unique shirt illustrating their experience of anti-black, anti-female and anti-LGB hatred and the hope that was pushing back.

EE Hope United Shirt Design Close-up

We at The Mill are artists, technologists and thinkers. But we’re not data scientists or sociologists. We knew it was imperative to shore up our design work with solid knowledge of online hate. So our first step in the project was to find a partner. We discovered HateLab, a team based at Cardiff University that specialises in discovering and assessing online abuse. Our relationship with HateLab and its founder Dr Matthew Williams turned out to be much more than a simple supplier partnership. Matt Williams opened our eyes to the realities of online abuse and how to combat it. He taught us how to understand the data, how best to search it out and how to represent it. We took this learning into our design process and we think the whole project is stronger for it.

EE Hope United Jersey Design Process

Anti-female Tweets mentioning Women’s team, measured by HateLab

Hopeful Tweets mentioning Women’s team, measured by HateLab With spreadsheets from HateLab we designed a generative art application to turn numbers into images. Artist/developer Seph Li worked with Mill Design Director Will MacNeil to build a system that could express the hate and hope contained in the numbers as powerful images illustrating the intensity of the social media dialog. As each player’s data set came in, a new design was automatically generated and reformatted to create the front and back of their shirt. The application can now respond whenever a new dataset is provided. This could be used for a huge range of online and offline applications for exploring and combating abuse on social media.

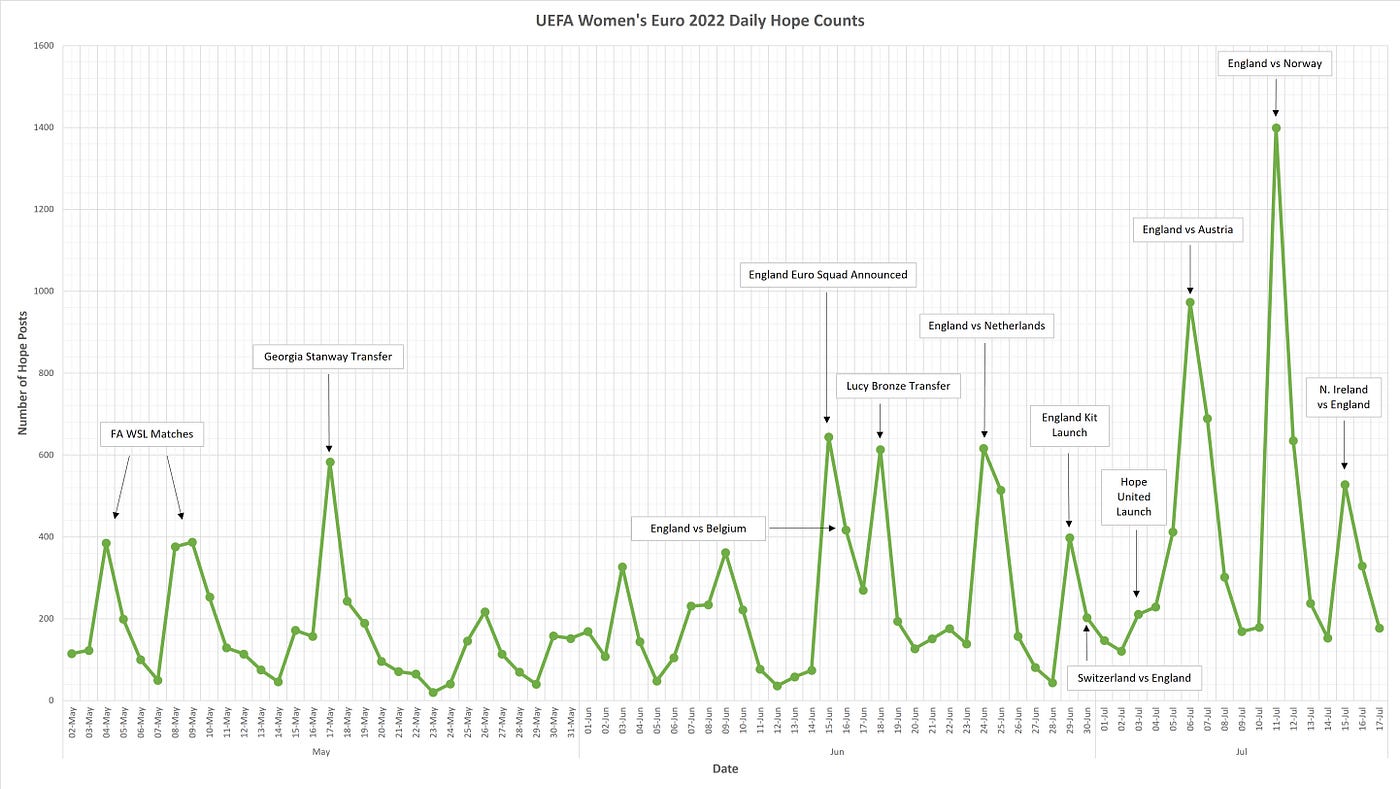

With the Women’s European Championship set to start in July, the Hope United Team focussed their attention on anti-female hate. The Hope United sponsors, EE, launched a campaign about sexist abuse aimed at female players, and how men could work to combat it. EE created a long form TV commercial based on the female players in the Hope United Squad, an outdoor media campaign and an online hub to educate visitors about sexism online. The Mill’s shirt design featured at the centre of the campaign. For us it’s been a rewarding journey of learning, creating and storytelling.

But this process isn’t limited to famous football players and large scale campaigns. We want to take this idea of customisation and personal storytelling and make it available to every single person who wants to share their lives and experiences. To see where we’re going, please read on!

_________________________________________________________________

Personalised trainer design Here’s a simple question that probably isn’t simple at all. What’s your favourite thing in the world? Leaving aside people and pets, what do you love? Is it something tangible like a sweater someone knitted for you, a letter from a great friend or a photo of your child? Or perhaps something you can’t really own like a piece of music or a place you visit? Then ask yourself this: would anyone else love it as much as you or in the way you do? Or is it your personal link to the object, and the stories and memories that come with it, that make it profoundly yours to love? Here at The Mill, we’re looking at what makes things valuable to us. Because a revolution in the way we acquire and own things is coming.

Professional content creators are, by definition, concerned about ownership. After all, if the things they make are to have financial value, the makers have to control how these items are bought and sold, or copied and distributed. So the producers limit the supply of the content they make in order to increase its value. If, for example, The Mandalorian were on free-to-air TV, no one would pay for a streaming service to watch it. As consumers, we’re well versed in contracts of service and ownership like this. But of course these agreements only work if the content creators are able to maintain control of the product or service. We’ve already seen what happens when someone finds a loophole. The advent of BitTorrent enabled file sharing services like Napster to circumvent the music recording industry’s model of buying and selling physical copies of music and sent the business into chaos. It took nearly a decade for the dust to settle. When it did, it revealed a new economic landscape: we rarely buy music now. Instead we subscribe to it.

This matters because we are fast approaching a revolution in social media: the Metaverse. Brands and platforms are scrambling to find ways to move our historical consumer habits, such as walking through a mall and buying a pair of trainers, into another dimension where the mall is virtual and the trainers are digital assets. When it comes to owning those assets, which could be anything from clothing and accessories to music, art, animation or 3D game characters, we’re most definitely in a period of flux, with creators searching out ways to designate ownership of their work in order to make it sellable.

It’s practically impossible to limit the sharing of a digital file, but it is in theory possible to document who actually owns the intellectual property. Enter non-fungible tokens (NFTs). NFTs are meant to allow artists to mint limited editions of digital creations as tokens on cryptocurrency blockchains. In turn these tokens can be bought and sold and creators can be paid for their work. But NFTs and the platforms that sell them are struggling with the simple fact that digital assets are easy to copy and share and extremely difficult to lock up in a vault. Theft in the NFT world is rampant. Artists have seen their work minted by strangers. Art buyers have been duped into buying ‘counterfeit’ works. And, perhaps the biggest flaw with NFTs, the tokens themselves don’t contain the digital file, just a link to it. If the server that the NFT links to goes offline, the token potentially becomes worthless. Throw in the volatility of the cryptocurrency world and the energy intensive process of mining coins and minting NFTs and the story just gets worse. Solutions will come, but for now NFTs are problematic.

So how do we sidestep the problem? We think the issue is in the false notion of scarcity. The whole premise of digital content is that it’s easily copied and shared. Why try to work against the fundamental strength of digital media? Where NFTs encourage a market of exclusive art at high costs and at high risk, we’re looking at doing the opposite and creating unique, customised objects that anyone can own and share freely. Our aim is simple: create digital and physical objects that have value not because they’re exclusive, expensive or difficult to acquire, but because they’re crafted for and by the people who want them. In other words, we’re going to make things that people genuinely love. And if they love what they make, they’ll probably feel pretty good about the brands that helped them make them.

Mustang Badge Designs This journey started for us several years ago with a unique project for Ford Mustang and AKQA. We built a web application that allowed Mustang enthusiasts to craft unique versions of the Mustang Pony emblem. These designs could then be reproduced in anything from a 3D printed badge mounted on a car to large format billboard advertising. As far as the user was concerned, the design process was simple and fun. They just played with the web app until they had something they liked enough to want to share. On the distribution side, things were similarly easy. Even though the system was able to produce a huge amount of custom content, managing it was relatively simple. At the heart of the web app was a procedural design system that expressed the users’ creations through a simple series of numbers. Creating the various outputs just required passing these numbers to the appropriate printing system (whether it be conventional printing or 3D). The end users were rewarded with something they crafted themselves.

We feel we’re seeing a new world of opportunities to craft custom digital and physical objects at scale. Behind the scenes, Mill artists have been diving deeper into customisation systems. Design Director Will MacNeil has been exploring data-driven artworks. His D’istral project links to a weather API and creates unique digital paintings based on the past or present weather in any city. Users simply enter a place and time and a unique painting appears. Will has expanded this system to ingest a much wider range of data inputs such as colour palettes scraped from Instagram accounts, or exercise data from a wearable. Want to create a painting based on the day you ran the marathon? We can do it. Or shoes embroidered with the colours from your holiday in Greece. We can do it.

We’re now exploring how this customisation might work with fashion brands. We’re looking at how we can take an existing piece of popular fashion design such as a North Face Down Vest and create meaningful alterations to customise the design and create digital assets. In time, users will take these digital garments with them into the Metaverse. Sports merchandise is another strong market for digital customisation. We’re researching systems to merge team fanbase data with sports attire. How many matches have you attended at Old Trafford? We’ll make a digital piece of clothing that beautifully illustrates your loyalty to Manchester United.

The interface for customisation could move well beyond the typical configurator we see currently. Users could be allowed to input anything they like from data sources like wearables or key dates to photographs, music, anything really. The creation process could take on much more than data input. We’re looking at using pose estimation to design a procedurally generated abstract outfit around your shape.

At the heart of this exploration is our concern about data ownership. While they may not realise it yet, most of the people we currently call consumers have in fact become the product. Their personal information is acquired, processed and bought and sold daily. In many cases, behind the wonderful connectedness offered by social media platforms is a well-concealed contract that grants the platforms an enviable bargain. Users get the benefit of well developed communications tools while the platforms extract an ever-growing stash of personal data that can be sold and traded.

We want to see a shift in this economy where users become masters of their own personal data. To start this process we want people to see how rich and valuable their personal data is. We think one way to do this is encourage them to interact with this information and use it to create personalised content. We see this as a benefit for both customers and brands. Brands will see a revolution in the way their customers interact with their products. And customers will find new ways to tell their own stories with the help of the brands they love.

-

I was once again asked to speak at Houdini Hive. This time my talk focuses on my personal project D'istral, which builds realtime data paintings based on the weather. I talk about the process of loading live data through an API into Houdini and then using that to create abstract paintings. Hope you like it!

-

I was originally meant to speak for SideFX as part of OFFF Barcelona. Sadly this event was cancelled due to COVID. Instead I ended up recording this presentation. It's mainly two parts. The first is about the sand and terrain work in The Mill's Al Jazeera Idents.. The second is an in-depth look at the concepts and workflow behind Stroke-it, a Houdini painting tool I develop.

-

This is a talk I gave on behalf of Maxon, in place of speaking in-person at IBC this year. My goal in the talk, aside from sharing some nice work from Mill Design, was to show how small personal projects can one day become large paid projects. Hopefully that comes across.